Piece by Piece: The Razing of the Chinatown at Cumberland

Piece by Piece

The Razing of the Chinatown at Cumberland

Update 2018-11-18: I’ve updated this post to correct misspellings and incorrect names of, or references to, individuals and organizations. This post now also contains more researched estimates of Chinatown’s peak population, and I have removed the comparison to the Chinatown in San Francisco in light of that reconsideration. We definitely have more research to do on these estimates – I pulled the 3000 figure in the original post from the back of a photo, but Imogene L. Lim pointed me to the 1921 census records as well as estimates in the archive that we’ll have to check out. All of these revisions were made thanks to notes and suggestions from her.

We’re grateful for Imogene’s time talking with the team about market gardens, Cumberland and BC Chinatown histories, and relationships. She works on food anthropology, does community-based research related to Asian Canadians on Vancouver Island, and is on the Coal Creek Historic Park Advisory Committee that is now mentioned in this post—among other great things. You can find more about her and her work at http://wordpress.viu.ca/limi/.

You can find a copy of the original post here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1agJcVQmhzutT8vBiwb6m8FbGZzuiygNWQRy_21H1Gc0/edit?usp=sharing

—

Cumberland is on the Unceded land of the K’ómoks, Sliammon, and Éy7á7juuthem. While I don’t write about those nations in this entry, I encourage you to think of the ways this destruction mirrors the erasure of Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island. British Columbia’s history is inherently Indigenous. Said destruction has come in many forms over time to Indigenous people, including a genocide that killed over 70% of the population. While this blog acknowledges the land that we traveled to, I urge you to go further. Knowing one history should link you to more. Let’s keep looking, asking, and listening together. Truth comes before reconciliation.

I also want to acknowledge the team who visited Cumberland were mostly white settlers or white-passing settlers who have had primarily white experiences in the world. This will always limit opportunities to see deeply and understand further. Any true understanding of place and culture must be understood from the people who have experienced it. We have not yet done that work outside of reading interviews from original Chinatown families.

—

Cumberland’s Chinatown and Japantown were dismantled piece by piece by people like you and me.

It started in the 60s. A decade that brought with it radical movements, economic power, a public awareness of history and preservation, and Canada’s Centennial. These factors mingled into a culture that collected tangible history. I think of the knick-knacks and curio shelves of my grandfather’s house, shelves of thick glass bottles and vintage auto store signage.

Curio Collecting was prolific and profitable, especially here in the Northwest. All ghost towns and abandoned places in BC, Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and California were affected by people going in and taking out what they could find. This didn’t really go away, it was amplified again by the US bicentennial and in recent years Pinterest’s commercialized love of shabby-chic. In the Coal Mining town of Cumberland it’s reported that hundreds of thousands of dollars of bottles were removed from throughout Chinatown and Japantown.

“The Cumberland bottle section of opium and medicine bottles is really unique. Up to now bottle collectors from the United States have assumed there to be a variety of approximately only 30 shapes and sizes in this category, I have just counted my 161st today.”

—Harry Lewis, Parksville, 1968 Cumberland Islander Newspaper

Archive Photo by Elad Tzadok

Abandoned places are in style and that has put them at risk of being erased.

It’s human to jump to the idea of preserving towns as historical monuments but there are over 150 ghost towns in British Columbia alone. Most of them were built to only last the duration of resource extraction, wooden buildings with no foundations. They’re remote! And white settler history of British Columbia is already abundantly documented, erasing other people who were in those townsites before Europeans.

Historical erasure comes in many forms.

In Cumberland, we went looking for the Chinatown to find it attached to the distressingly named Japtown and Coontown. We didn’t know those towns existed ahead of time and we were trying to find the history.

While there is very little left of Chinatown and Japantown, there are no traces of the 40 person Black settlement. I don’t know when the last person lived there, I don’t know their family names, I don’t know about their lives. I’ve only seen the town site referenced in one newspaper article and a book by Vancouver Island writer, T.W. Paterson. Of course, I’ve added it to the list of things to research but it begs notice that there is so little accessible.

Japantown has a different end – the townsite is now covered in 31 cherry trees, planted by the Coal Creek Historic Park Advisory Committee with support from the National Association of Japanese Canadians to represent the 31 families who were forcibly removed from their homes during Japanese Internment. Originally the area had over 500 Japanese settlers. When internment ended in 1949 (four long years after the war had ended) those families had nothing and limited reason to return to their hometowns. Those who did return would come back to burned buildings, hostility, lost businesses, and very few neighbours.

Chinatown is the largest in size. In the 1920s, somewhere between 800 and 1200 Chinese settlers lived on the site. Today, young birches have cracked their limbs through the gravel paths. The swamp water has slicked its way back up to high ground since Cumberland’s Chinatown was razed in 1968. Originally the area’s water was diverted and set through a narrow slough to flood the lower fields.

It’s hard to see how this place could be anything more. It’s rare that a ghost town has so few traces of its origins. Truly, we’re used to rubble, clotheslines hanging in trees, banker’s safes blown open and strewn, buildings and boards. But here, in Cumberland, only coal tailings remain. We kick around for the day and find a porcelain jug in an obvious dumping pile, a few bottles, century-old orchard trees, a baseball diamond, and a few scattered bricks. That’s it.

In 1960 it’s reported that about 40 people were still living in the area, by 1967 the number had dropped significantly; however, the town wasn’t empty when it was razed. The remaining Chinese settlers were evicted from their homes. Only one building was left standing, Jumbo’s Cabin, it was moved to the top of the road and effectively displayed.

A small irony is that Jumbo’s Cabin is perhaps the only building in the entire town site that was built by White Settlers.

This razing came after an attempt to preserve it as a heritage site in 1963, the City of Cumberland passed through the idea but never found the funds.

In 1968, the same Harry Lewis I quoted above, was leased the townsite by Weldwood Canada. The land had always been owned by different Coal Companies. He was a history lover and was in the midst of building up Parksville’s BC Coast Pioneer Village. He said “The village will house buildings of local historical importance – some of which are just merely representative of former pioneer homes.” -Cumberland Islander.

He was offended that people thought ill of his leasing the Chinatown and Japantown site from Weldwood. “Most people around here have the idea that I’m out here to make a pile of money for myself and then get out. They don’t realize that I’m doing them some good. I think that the people of British Columbia are darned lucky that there are some people – and few mind you – who are interested in preserving their country’s heritage.”

That “good” was the building of the Pioneer Village in the Parksville. He fundraised the project by charging $2.50 per day to have people come into the Chinatown site and collect. They could take anything they could find.

The building of a new heritage site, with the intention of preserving local history, was funded by the literal dismantling and selling of another, while people still lived there. This new museum would hold mostly the history of white settlers. That’s erasure.

To his credit Harry Lewis does also say “One can only guess what might have been done with this place (Chinatown) if it had been rescued even up to five or six years ago.” None of this was done with consultation of the people who were still living there. They didn’t own the land and weren’t considered despite being living testaments of the heritage people saw as significant.

When we think of BC’s History, a white miner in plaid, sloshing a gold pan in a creak appears much quicker in our minds than Cumberland’s Chinatown. Physical artifacts hold more weight than an oral history reported by people who lived it.

So what does the word “heritage” mean to you?

I thought titling this article “Heritage is White Nationalism” wouldn’t be particularly approachable to many people. Or funders. Hopefully they didn’t make it this far.

One person’s “heritage” could erode another’s piece by piece. This reality gets darker when we reflect that the legacy of the razed townsite at Cumberland is all that’s left of three distinct towns with three distinct histories.

Photo by Elad Tzadok

Fail Forward #1

Fail Forward #1

A Weekly Recap of POPULOUS MAP

We know that data tells stories, here’s ours.

This week:

Sunday, March 4, 2018

Written from:

Unceded Territory of the Qayqayt.

New Westminster, BC

Thought of the week: This week we became a community working towards a common goal. This morning at Lost + Found Cafe I saw our future. It was beautiful.

Feeling of the week: Excitement

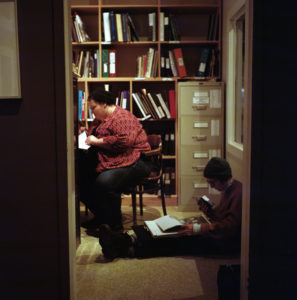

Photo of the week:

“Data Entry at Lost + Found Cafe.”

Website:

1: Website Soft Launch

11: Timeline or history websites added in the “To Add” section

8 of 156*: Timelines Added

1: About statement written

1: Contribution Typeform made

0: New Typeform contributions

0: “Read More” sections added

1: Video recorded

0: Videos edited

0: Videos released

308: Data points formatted to be uploaded

528: Data points uploaded to map

2: New Filters

(Disability, Institution)

1: In progress Community Agreement

1: Blog post

Events:

1: Data Party

10: Volunteers

1: Debrief

46: Hours of shared work

0: Events lead by the Populous Community

Internal Outreach:

1: Hour speaking on phone with Knowledge Keepers

6: Hours spent working on projects that promote reciprocity

5: Hours spent writing “How we made Populous Map” document

External Outreach:

2: Hours spent responding to emails

2: Hours spent developing curriculum pieces

2: Coffee dates

1: Media pack developed

14: Names added to mailing list

Funding:

1: Grant applied for

https://bac-lac.fluidreview.com/

6: Hours writing grants

1: Patreon developed

27: Per month raised through Patreon

Field Work:

0: Field Work Trips

1: Field Work Trip Planned

Social Media:

16: New page likes on Facebook

269: Total Facebook Likes

All names reserved on core sites

@PopulousMap

*Always growing

Brian Eno Oblique Strategy Card: “Embrace the Flaws.